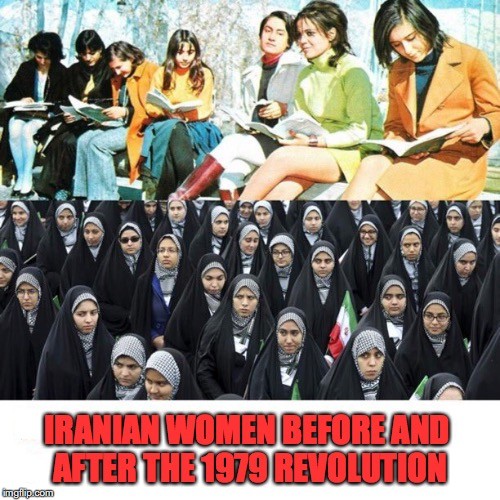

The message of course being that before the Islamic Revolution, women in Iran were free but now they are oppressed (something similar is said about Afghanistan).

This simplistic view is unfortunately contradicted by reality:

"In 1967 the Family Protection Act (FPA) reformed family law. According to these reforms, a man could marry a second wife only with the permission of the court. In 1975 the consent of the first wife was added, unless she was unable to have sexual relations with her husband or unable to bear children. The first wife also had the right to seek divorce if her husband married a second wife. A woman could apply for divorce if her husband was unable to have sexual relations with her, was unable to provide for her, ill-treated her, suffered from a contagious disease, abandoned her or was insane. Divorce could be obtained only in the civil courts. The 1975 Act also raised the age of marriage to 18 for women and 20 for men. In 1977 abortion was legalised, but married women had to obtain their husband’s written consent. Unmarried women upon their written request could have an abortion.

These reforms were ambiguous. For example, consent to a husband’s polygamy was often given because the woman feared her husband’s violence. The reforms did not contradict shariah law, but left women as inferior beings in many ways. Women could not be employed on the political staff of the foreign ministry; in the course of the land reform which began in 1962, land was sold only to men. The man was still the head of the family: a wife was still legally forbidden to hold a job which the husband considered damaging to the dignity and prestige of the family; a woman could not leave the country without the permission of her husband or father; the wife was not free to choose her place of residence. A woman, regardless of her age, had to obtain her father's permission to marry for the first time, at divorce, the husband retained custody of the children — even with the husband‘s death, it was the husband's father who automatically became guardian of the children and not the children's mother. According to ghisas (the law of retribution), a part of shariah law, it was not a criminal offence for a man to kill his wife for the defence of his dignity. The Muslim system of polygamy, under which a man can have four wives, remained legal, although the number of polygamous marriages declined for economic reasons and strengthened the nuclear family relationship. Sighe (temporary marriage), when a man lakes a woman as his wife for a limited period, continued to be sanctioned by the clergy...

Women (except nurses) were forbidden to work between 10 pm and 6 am and to do heavy work, as they were considered weak...

The shah's rhetorical support for women's rights and gender equality issues was more consistent with his concern to project a Westernised image to the West rather than with a genuine concern for gender equality... Paradoxically in 1978, under the pressure of conservative Islamists, he reduced the age of marriage for girls from 18 to 15 and dropped the post of Minister of State for Women's Affairs...

The shah’s state, in the 1960s and 1970s, entitled only a minority of women to some reforms. The impact of the modernisation of state and society, based not on an indigenous model but as part of the Pahlavi Shah’s process of Westernisation, was particularly painful for the majority of the population. They had to endure Westernisation and at the same time observe the absolute Islamic values of segregation, including the wearing of the chador (long Islamic cover) as dictated by their families, especially male relatives who regarded the culture of modernity based on Western model as horrific and inappropriate for their women. For respecting these values and traditions, on the other hand, they had to pay the heavy price of being labelled as backward in schools, universities and workplaces. These women were torn between their families’ traditional religious values and a society which promoted Western values, including the wearing of the latest European fashions. They were expected by their families to leave home wearing the chador as a sign of honouring their Islamic tradition, but outside of the home they felt rejected for wearing the chador, which was assumed to be a sign of backwardness... many others took a defensive position and wore the hijab as a sign of protest at the uneven economic, political and social change...

The majority of women of different social classes and with different levels of religious observance participated on a mass scale in the 1979 revolution. During this period millions of women took part in daily demonstrations, most wearing the black chador."

--- Women, Power and Politics in 21st Century Iran / Tara Povey

(more [previously shared]:

How the Muslim World Lost the Freedom to Choose – Foreign Policy

Islamic feminism and miniskirts: The veiled truth about women in Iran)

Keywords: Tehran was not Iran

Addendum: More from the same:

"Reza Shah’s Westernisation of economy and society attracted a section of the society which rapidly became the new bourgeoisie and the professional salary-earners. The Islamists lost much of their economic and political power and this created intense hatred for Reza Shah among large sections of the population who identified with the Islamists and were excluded from the process of socio-economic and political development...

Under the dictatorial regime of Rexa Shah the power of the Islamic clergy declined. However, the power of Islamic ideology on issues relating to women and the family remained strong (Paidar 1997: 120—23). Most feminists and women’s rights activists in this period, therefore, concentrated on female education. health, and unequal marriage and divorce laws. They only indirectly argued about the question of the veil and women‘s right to vote. Some leading members in this period were practising Muslims and considered the teaching of Islam necessary. But they were critical of the way women were treated. They argued that child marriage and not allowing women to be educated and to participate in public life was un-Islamic.

During 1935—6 Rexa Shah, as part of his Westemisation of society. campaigned to force women to abandon the veil in all public places. In 1937 he prohibited the celebration of 8 March, International Women’s Day, and declared 7 January the first official day of the public unveiling campaign as the Iranian Women’s Day. Women’s responses varied; many considered the compulsory unveiling and forcing women to wear Western-style female hats to be a case not of women’s emancipation but of police repression. Others celebrated the occasion since many women’s rights activists were disappointed with the secularists and Islamists, who had failed to introduce female suffrage and the reform of women’s education and employment...

Reza Shah’s reforms were based on massive repression of all political groups, from communists to liberals, of protesting clergy, trade unionists, women‘s organisations and minority nationalities. The aim of Reza Shah's reform was to centralise state power, which meant keeping the clergy and religious institutions under strict control. Despite this. the reforms in relation to women and the family remained ambiguous and not necessarily in contradiction with basic shariah law. For example, the age of marriage was left to depend upon local interpretation of the age of puberty, a wife had the right to object to her husband marrying another woman, and the man had to inform his wife if he intended to do so. But in many parts of the country civil courts did not exist and the local clergy dealt with marriage and divorce issues according to their own interpretation of the law. The law continued to regard men as superior, and they retained their Muslim privileges of having up to four wives at a time and divorcing at will. A man was still recognised as the legal head of the family and enjoyed more favourable inheritance rights. Women remained deprived of the fight to vote and could not stand for election. Moreover, the limited reforms led to a long-lasting political conflict between the Islamists and the Pahlavi regime...

Many [women] took a defensive position and wore the hijab as a sign of protest at the uneven economic, political and social change (Tabari and Yeganeh 1982: 9—10). They detested the Pahlavi regime under which they were considered backward and had experienced nothing but humiliation because of their commitment to Islamic values. They had felt marginalised because they were ideologically and materially debased, degraded and neglected. The Pahlavi state ideologically restricted their access to secular education and employment. Therefore they did not benefit from the limited reforms which undermined some aspects of patriarchal gender relations...

The majority of the population related more to the Islamists modernists than to the secular left and the nationalists (Rostami-Povey 2010b: 46—80).

The majority of women of different social classes and with different levels of religious observance participated on a mass scale in the 1979 revolution. During this period millions of women took part in daily demonstrations, most wearing the black chador. As discussed above, many young women of these families had been forced to imitate Western values when they went to work or to university, while their families insisted that they should behave according to the religious values. This imbalance resulted in a crisis for them. Their support for the Islamists was a political act against alienation and dissatisfaction, reflecting their anger. More importantly, as I learned when I interviewed a number of these women. behind the passive image given to them by the Western media — they were serving God and men — was another reality, of strong women taking initiatives, organising and raising the consciousness of men and women about injustice and inequality. These women marched confidently, rejuvenated and glorified by Islamic values. They were excited and moved not just by their belief in Islam but also by their involvement in political activities acknowledged and supported by the Islamists (Rostami-Povey 2010a: 123—5)."