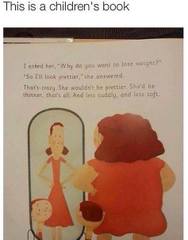

"'This is a children's book'

I asked her, "Why do you want to lose weight?"

"So I'll look prettier," she answered.

That's crazy. She wouldn't be prettier. She'd be thinner, that's all. And less cuddly, and less soft."

So a recognisably obese woman is told that she won't look prettier if she loses weight.

And also that she'd be less cuddly and soft if she were thinner.

In other words, it is better to be obese than non-obese.

Of course, some people claim that (childhood) eating disorders are a bigger problem than (childhood) obesity, and that discouraging obesity will cause an increase in eating disorders. This is a very problematic claim, because:

1) Obesity prevention actually *reduces* eating disorders

Does Obesity Prevention Cause Eating Disorders?

"There are data to suggest that our recent societal focus on obesity prevention has not led to a discernable increase in eating disordered behavior. Overall trends measured by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that there has been no significant change over time from 1995 to 2005 in the percentage of high school students who took laxatives, diet pills, powders, and liquids or vomited to lose weight or prevent weight gain. Although the prevalence rates are concerning (i.e., 4.5%-6% for vomiting and laxative use, 6.3%-9.2% for diet supplements), there is no evidence that increased media and professional discussions about childhood obesity have been associated with a concomitant increase in pathological findings.

Further data comes from the evaluation of Arkansas’ statewide multicomponent effort to reduce childhood obesity, which included BMI reports. Three-year follow-up data indicate that BMI has leveled off, and there has been no increase in youth reports of taking diet pills, exercising excessively, starting diets, or weight-based teasing. This suggests that large-scale policies can be implemented responsibly and successfully prevent a BMI increase without unintended consequences.

A handful of controlled trials have also addressed this issue. Schwartz and colleagues evaluated a school intervention implementing nutrition guidelines for snack sales in middle schools. Students were assessed for eating behaviors, desire to lose weight, and dieting behavior before and after intervention. Student nutrition at school improved in only the intervention schools, but body dissatisfaction in both conditions increased over time. Because the intervention and comparison schools did not differ, it is unlikely that the changes in food policy played a causal role in this increase...

Very strong evidence that eating disorder and obesity prevention can be done together comes from Austin and colleagues, who have demonstrated that broad-based obesity prevention programs can actually be helpful in efforts to decrease eating pathology. The Planet Health study was designed to promote nutrition and physical activity and decrease television viewing in 10 middle schools. The 5-2-1 Go! study aimed to promote nutrition and physical activity and decrease overweight in 13 middle schools.8 Both studies assessed disordered weight-control behaviors, such as dieting to lose weight, self-induced vomiting, laxative use, and taking diet pills. In both programs, girls in the intervention schools were less likely to engage in these behaviors at follow-up than were girls in the control schools...

Body dissatisfaction rates are high; one study found that 40% of 9- to 11-year-old girls are worried they are fat or will become fat. Although disturbing, the truth is that many of them may be right."

2) The health burden of obesity dwarfs that of eating disorders

For example, in Australia,

Eating Disorders in Australia

"Eating disorders are the 12th leading cause of mental health hospitalisation costs within Australia. The expense of treatment of an episode of Anorexia Nervosa has been reported to come second only to the cost of cardiac artery bypass surgery in the private hospital sector in Australia.

Bulimia Nervosa and Anorexia Nervosa are the 8th and 10th leading causes, respectively, of burden of disease and injury in females aged 15 to 24 in Australia. This is measured by disability-adjusted life years."

Burden of overweight and obesity (AIHW)

"High body mass was estimated to be responsible for 7.5% of the attributable burden of disease and was third in line behind tobacco and high blood pressure"

(High body mass was the third highest factor responsible for disability adjusted life years, and tobacco and high blood pressure had only slightly higher weights)

Addendum: Another example of glorifying obesity, which some people claim does not exist