"One of the best-known books about my cohort, for instance, is titled Generation Me. The New York Post called us “The Worst Generation,” while USA Today noted that we are “pampered” and “high maintenance.” Earlier this year, a New York Times op-ed called us “Generation Why Bother,” noting that we’re “perhaps…too happy at home checking Facebook,” when we could be out aggressively seeking new jobs and helping the economy recover. The fact that up to a third of 25-34 year-olds now live with their parents only supports these gripes.

To many, the core problem of this generation is clear: we’re entitled. I don’t deny these behaviors, but having recently finished researching and writing a book on career advice, I have a different explanation. The problem is not that we’re intrinsically selfish or entitled. It’s that we’ve been misinformed.

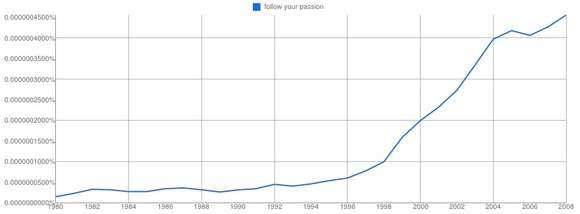

Generation Y was raised during the period when “follow your passion” became pervasive career advice. The chart below, generated using Google’s N-Gram Viewer, shows the occurrences of this phrase in printed English over time.

Notice that the phrase begins its rise in the 1990s and skyrockets in the 2000s: the period when Generation Y was in its formative schooling years.

Why is this a problem? This simple phrase, “follow your passion,” turns out to be surprisingly pernicious. It’s hard to argue, of course, against the general idea that you should aim for a fulfilling working life. But this phrase requires something more. The verb “follow” implies that you start by identifying a passion and then match this preexisting calling to a job. Because the passion precedes the job, it stands to reason that you should love your work from the very first day.

It’s this final implication that causes damage. When I studied people who love what they do for a living, I found that in most cases their passion developed slowly, often over unexpected and complicated paths. It’s rare, for example, to find someone who loves their career before they’ve become very good at it — expertise generates many different engaging traits, such as respect, impact, autonomy — and the process of becoming good can be frustrating and take years.

The early stages of a fantastic career might not feel fantastic at all, a reality that clashes with the fantasy world implied by the advice to “follow your passion” — an alternate universe where there’s a perfect job waiting for you, one that you’ll love right away once you discover it. It shouldn’t be surprising that members of Generation Y demand a lot from their working life right away and are frequently disappointed about what they experience instead.

The good news is that this explanation yields a clear solution: we need a more nuanced conversation surrounding the quest for a compelling career. We currently lack, for example, a good phrase for describing those tough first years on a job where you grind away at building up skills while being shoveled less-than-inspiring entry-level work. This tough skill-building phase can provide the foundation for a wonderful career, but in this common scenario the “follow your passion” dogma would tell you that this work is not immediately enjoyable and therefore is not your passion. We need a deeper way to discuss the value of this early period in a long working life.

We also lack a sophisticated way to discuss the role of serendipity in building a passionate pursuit. Steve Jobs, for example, in his oft-cited Stanford Commencement address, told the crowd to not “settle” for anything less than work they loved. Jobs clearly loved building Apple, but as his biographers reveal, he stumbled into this career path at a time when he was more concerned with issues of philosophy and Eastern mysticism. This is a more complicated story than him simply following a clear preexisting passion, but it’s a story we need to tell more.

These are just two examples among many of the type of nuance we could inject into our cultural conversation surrounding satisfying work — a conversation that my generation, and those that follow us, need to hear. We’re ambitious and ready to work hard, but we need the right direction for investing this energy. “Follow your passion” is an inspiring slogan, but its reign as the cornerstone of modern American career advice needs to end.

We don’t need slogans, we need information — concrete, evidence-based observations about how people really end up loving what they do."